I’ve been on a lemonade kick lately so I decided to hunt for a new recipe in 19th century cookbooks. I am rarely shocked anymore by the things I find in these old books, but I’ll admit that the discovery of early instant lemonade powder mixes took me by surprise. I don’t know why it should – it makes perfect sense that travelers and picnickers would have wanted an easy portable drink option then just as they do now. Instant and imitation foods may seem like a modern concept, but there are a lot of products that have been around much longer that we realize.

I flipped through a large number of digitized texts in search of different variations and found that there really were only three:

- The most common variation is probably the one that is most similar to modern powdered mixes: just sugar, lemon essence, and citric/tartaric acid.

- Many of the home cooks wanting to avoid imitation flavors opted for the less shelf-stable version, which was sugar, citric acid, and actual lemon rinds and juice.

- A third version that I found mostly (but not exclusively) in medicinal or pharmaceutical books is something called “aerated lemonade,” which adds bicarbonate of soda to lemon essence, sugar, and citric/tartaric acid.

All of the mixes are meant to be dissolved in water. Those of the bubbly “effervescing” variety could be added to soda water instead. Many recipes can be stored in jars, but some recommend dividing the mixture into individual portions, wrapped in paper or packets much like the products found in stores today.

There wasn’t a noticeable change in the recipes over the span of the 19th century; the ingredients and preparation methods in the 1890s were roughly the same as they were in the 1810s. The only real change was the measurements as loose granulated sugar gradually replaced the packed sugarloaf.

The oldest one I found, at least amongst the books available in my favorite digital repositories, is from 1794. This “dry lemonade” was recommended as a means to avoid getting scurvy on long voyages.

Source: Practical observations on the operation and effects of certain medicines, in the prevention and cure of diseases to which Europeans are subject in hot climates, and in these kingdoms…by Richard Shannon (1794). See page 335.

Fun fact: Tartaric acid as we know it was created in the 1760s, followed by citric acid in the 1780s. Both are naturally occurring acids that were discovered as far back as the eighth century, but it took a thousand years to develop the chemical processes that isolated them as pure substances for use as preservatives and flavoring agents.

I’ve gathered some additional sources and screenshots of recipes at the end of this post. For now, let’s get to my recreations of two common types of “portable lemonade.”

The Recipe(s)

I really wanted to try both the imitation lemonade powder and the real lemon mix, so I chose one of each to highlight for this post.

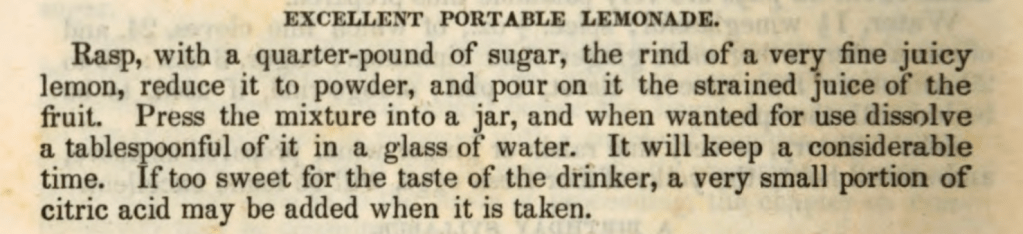

First up is the real lemon variation from Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery in all its Branches (1845). The actual title is ridiculously long, but the full book can be accessed online here. Eliza Acton was a prolific English writer and was well-known for her poetry and her detailed cookery guides.

It is important to note that during this time refined sugar was typically sold in the United States and UK in sugarloaves or sugar cones. These were tightly packed molds of sugar that would have to be broken up with tools like sugar nips or cutters for use in recipes.

While you certainly could use granulated sugar for this recipe without losing much, this particular version will be much better with a sugarloaf or cone if you can find one. I was going to make one at home until I found a German Zuckerhut in a European grocery store nearby. The brand of Zuckerhut I bought is half a pound, so I doubled the recipe.

Ingredients

- 8 oz. sugar (1/2 a pound or approximately 230 grams). Sugar cone highly recommended.

- 1-2 lemons

- 1/8 tsp. citric acid for each serving or to taste.

Directions

If you are using a sugar cone or loaf, rub the rind of one lemon directly onto the sugar to deposit the oils. Reduce to powder using a mortar and pestle, or some other method. I put the cone in a ziplock bag and pulverized it with a mallet. If using loose sugar, finely grate the rind of one lemon and blend.

Strain the juice of a lemon, pour onto the sugar and mix. Be sure to strain the juice to remove seeds and pulp. Store the mix in a jar.

When ready to serve, add a tablespoon of the mix to 3/4 cup of water in a glass. Add 1/8 tsp citric acid per serving and stir until dissolved. Add more citric acid if you would like your lemonade to be a bit more tart. Ratios can be adjusted to taste.

I squeezed two lemons because this made sense for the amount of sugar being used after doubling the recipe. The only problem with this is that the sugar ends up very wet. I don’t think this is a bad thing as far as flavor goes, but I would probably use less liquid next time.

I’ll be honest that I do not know what texture this mix is supposed to be. The recipe says to “press it” into a jar, which implies that it shouldn’t be as dry as granulated sugar, and it definitely shouldn’t be a liquid. I would imagine it will keep better long-term if it is more on the powdery side, but it won’t be as flavorful. In the end it didn’t matter that much because we used it all within two or three days.

Acton’s “excellent” portable lemonade recipe truly is excellent, but more on that later.

Next up is an 1893 artificial lemon variation using lemon essence instead of the lemon juice and rind. There are a lot of these in earlier texts, but most use bulk measurements that don’t scale down very well. I tried one from 1844 that ended up with some complicated weights, and it didn’t turn out great anyway so I’m highlighting this one instead.

This recipe is from The House-Keeper and Farmer’s Companion by J.D. Heard (1893). You can find it here

Ingredients

The measurements are halved so the mix fits in one jar. I recommend using a kitchen scale.

- 1 pound of sugar (approx. 2 cups)

- 1/2 ounce of tartaric or citric acid (approx. 4 tsp)

- 1/8 ounce of lemon essence (approx. 1 tsp)

Directions

Combine ingredients and blend well. Keep it stored in a jar. To serve, add a tablespoon of the mix to each 3/4 cup water and stir until dissolved. Adjust the ratios (water, mix, citric acid) to taste.

This variation is extremely easy to make. The texture of the mixture is pretty much what you would expect, though not as dry as modern instant lemonade mixes. I imagine it will store and travel really well.

This is a decent artificial lemonade, which again isn’t necessarily bad if you like that sort of thing. I can’t completely verify this without a side-by-side taste test, but my family says it tastes like Crystal Light lemonade.

The Verdict

There is no competition between these two recipes. The winner is easily the real lemon variation. My son and his friend loved it so much that the batch I made didn’t last very long at all. And that is saying something because the children in this house are generally wary of the historic recipes I ask them to test.

The imitation one certainly has its benefits, particularly in how easy it is to make and it will probably last longer if stored properly. I don’t really like it though, but I don’t particularly enjoy artificial lemonade to begin with.

More Recipes

Here are a few more recipes for your reading pleasure.

Recipes were regularly copied and reprinted in multiple cookbooks, though it is unclear how much of this was considered plagiarism. This is the exact recipe published in J.D. Heard’s 1893 recipe above, but with one notable change. This version calls for 10 ounces of tartaric acid, while the one I tested calls for only 1 ounce. Could this version be a measurement typo?