Hattie Burr was forty-five years old when she published the first of many women’s suffrage fundraising cookbooks in the United States. Although it would take three more decades of waiting, she fortunately lived to see her suffrage dream come true.

It was common practice after the Civil War for church and humanitarian groups to publish and sell cookbooks for charity, which were compilations of recipes submitted by women – and sometimes men- in the community. Before social media, church and social clubs were vital for women to network and rally support and funding for various causes. So it makes sense that suffragettes and supporters of political reform would adopt these same methods to push for women’s suffrage in the United States. Publishing a cookbook was not only an excellent way to communicate directly with other women, but it also sent a clear message that equal rights were not a threat to the home and domestic life.

In 1886, when The Woman Suffrage Cookbook was published, only Utah and Wyoming territories allowed women to vote. Wyoming technically passed a suffrage law in 1869 but did not hold an election until after Utah in 1870, making Utah the first in the nation to put the law into practice. Despite this, progress was slow in the eastern part of the nation. 1886 was also significant for being the year the first report supporting a woman suffrage amendment was submitted to the U.S. Senate. It would later be submitted again in 1915 as the “Susan B. Anthony” amendment, five years before the historic 19th amendment granted the universal right to vote.

The Woman Suffrage Cookbook contains a wide variety of recipes for all kinds of dishes and skill levels, from a single line of instructions for Golden Toast to the more labor-intensive Feather Cake and a Plum Duff that takes anywhere between four and seven hours to steam. Most are very common 19th-century recipes, but some are quite fancy and others are what even the contributors considered “old-fashioned.” And just in case the reader forgets what the point of the cookbook is, she can try her hand at “Mother’s Election Cake” and “Rebel Soup.”

As an added bonus, one section of the book includes recipes and directions for making soap and cleaning mildew, among other things. Health tips are offered by Mary J. Safford, M.D. and Dr. Vesta Miller, and a group of physicians (all women) contributed tips on the caring and feeding of invalids.

To the modern reader it may seem odd that suffragists fighting for their rights outside of the domestic sphere would do so by sharing household tips, but The Women Suffrage Cookbook is much more than just a compilation of recipes and hints for housewives, it is a symbol of unity and activism within the one domain where women had a voice: the home. Most of the contributors were prominent American women including well-known suffragettes, journalists, doctors, ministers, and teachers. An entire section of the book contains “eminent opinions on woman suffrage” shared by politicians, philosophers, authors, and other women and men who supported the rights of women to engage in political life.

The Recipes

There are a lot of recipes in the book that look interesting, but I decided to choose three that I normally would have overlooked in favor of a dessert or something hilariously unappetizing. All three use pretty standard ingredients and are a sort of 19th-century twist on three foods that many Americans still eat regularly: hard-cooked eggs, mashed potatoes, and jelly.

A digital copy of the book can be accessed here.

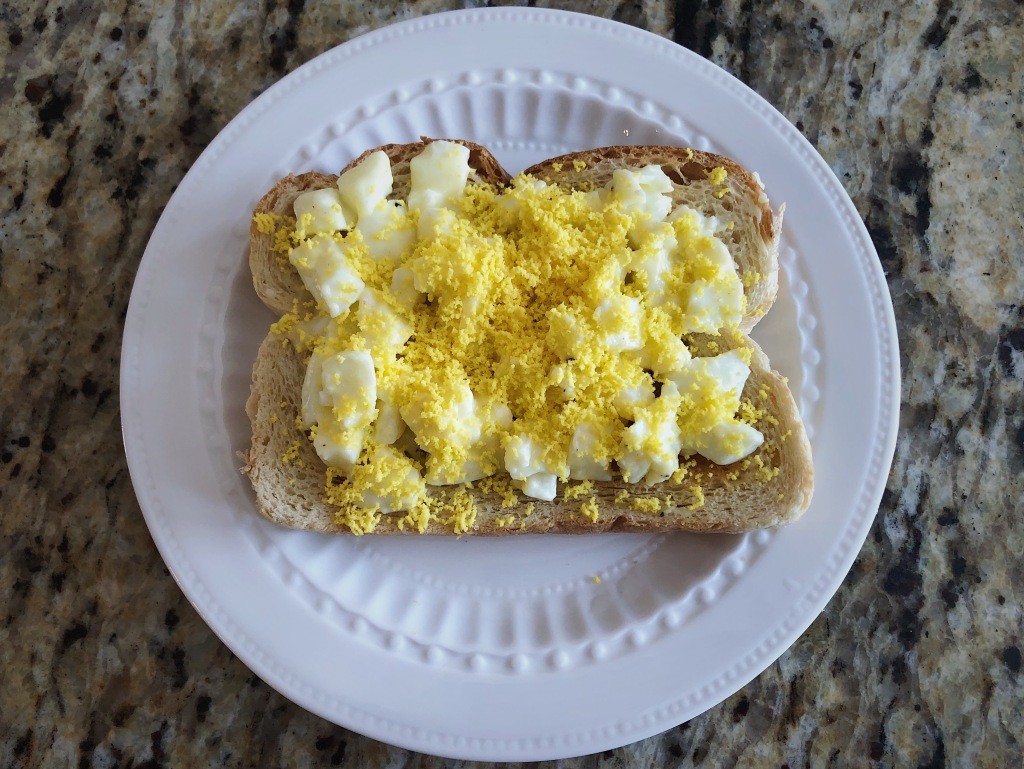

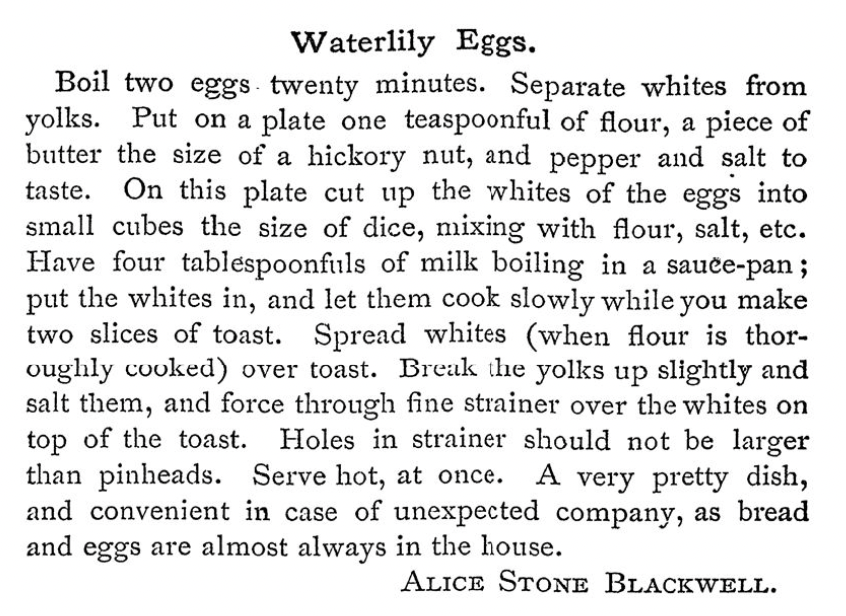

Waterlily Eggs

Ingredients:

- 2 eggs

- 1 tsp. flour

- 1 T. butter

- pepper and salt to taste

- 4 T. milk

- 2 pieces of toast

The instructions in the original recipe are very clear, but I will sum it up for you in four easy steps:

- Boil eggs and separate the whites from the yolks.

- Cut up the whites and mix with the flour, butter, pepper and salt.

- Cook the floured and seasoned whites in boiling milk for 3-5 minutes or until flour is cooked.

- Spread whites on toast and sprinkle sieved/crumbled yolks over the top before serving.

An important historical note: This recipe was contributed by Alice Stone Blackwell. If you have never heard of her, perhaps you have heard of her mother Lucy Stone, a highly influential abolitionist and suffragette whose name is often connected with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Alice Blackwell was the editor of The Woman’s Journal and a founder of the Massachusetts League of Woman Voters. You can read a little more about her here.

The Verdict

Waterlily eggs remind me a lot of a 1916 Creamed Eggs and White Sauce recipe I did a while back, but way less creamy. Both are good but I prefer this one!

Perhaps I am lazy or just coddled by easy access to fast food and grocery stores, but I wouldn’t say this is particularly “convenient in case of unexpected company” unless you already have hard-cooked eggs on hand. Although I really do like this recipe, I am not sure I would randomly serve it to my house guests unless they are already aware of the types of food we eat around here.

Overall, this is a good and very simple snack or appetizer that might be fun to try when you need something different to do with boiled eggs! I will warn you, however, that the measurements do not yield enough food to fill two standard-sized pieces of toast. You would be better off using homemade bread or cutting the toast into smaller pieces. It should serve one hungry person or two peckish people.

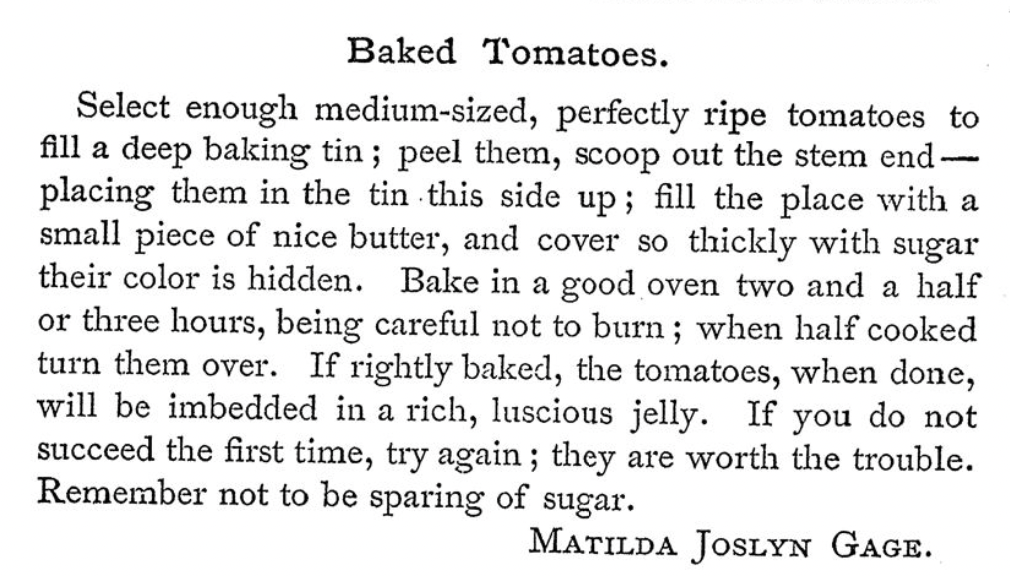

Baked Tomatoes

Matilda Joslyn Gage was another prominent suffragist who co-founded the National Woman Suffrage Association with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and she later formed the Woman’s National Liberal Union. She was raised by abolitionist parents and grew up in a home that was a station on the Underground Railroad, which was only the beginning of her lifelong passion for political and social activism.

Ingredients:

- 4 medium to large tomatoes

- 1-2 T. butter

- 1 cup of sugar or more to taste

Directions:

Peel and scoop out the stem and seeds of each tomato. Tomatoes are usually blanched for peeling, but I just skipped that step and peeled them the slow way. After blanching or not blanching, cut around the stem at an angle and put it out, then scoop out the tough section of seeds. Do not hollow out the tomato like you would if you were stuffing them. Leave as much of the flesh inside as you can.

Place the tomatoes stem side up in a deep baking dish. I used a bread pan, which worked well for the size of tomatoes I used. Put 1/4 or 1/2 of a tablespoon of butter in each of the tomatoes. The easiest method is cutting a tablespoon off of a good quality stick of butter, then quarter it. Double it if you are using very large tomatoes.

Sprinkle roughly 1/4 cup of sugar over each tomato, but you may have to adapt to the size of your tomatoes and your dish. Matilda Gage specifically says to not be sparing of sugar, so do your best to cover the tomato so thickly that the color is covered or at least very muted. I felt like I was using a lot more sugar than I should and much of it dissolved when it touched the tomato, making it difficult to completely hide the color.

Bake in a 325 degree oven for about 90 minutes, then flip the tomatoes over. Bake another 90 minutes or until done. The tomatoes should be not burned, and the liquid should be a thin jelly. Take the pan out to cool and the jelly will harden somewhat. I don’t know if I was supposed to do this, but I used the back of a spoon to very gently smash down the tomatoes while they were still hot. They broke apart with almost no effort on my part and blended in with the rest of the jelly, making it much easier to scoop and eat. If you want, carefully pour it into a jar and let it cool before storing it in the fridge for up to a week.

The Verdict:

I really did not know what to expect with this one but I will admit that I was shocked by how well this recipe turned out. Tomato jelly is absolutely delicious and if you haven’t had the pleasure of tasting something like it, you must give this a try. There may be better cooking methods out there, and modern recipes for slow roasted tomato jam with additional ingredients, but I don’t think I would change a thing. This recipe is perfect just the way it is.

The jelly goes really well on bread, but my favorite combination was with some brie or white cheddar cheese on crackers. I suppose you could also not mash the tomatoes down like I did and just eat them on their own like a oven-stewed tomato, but these don’t hold their shape very well. Unless I made these completely wrong, it really makes more sense to eat it as a thick jam.

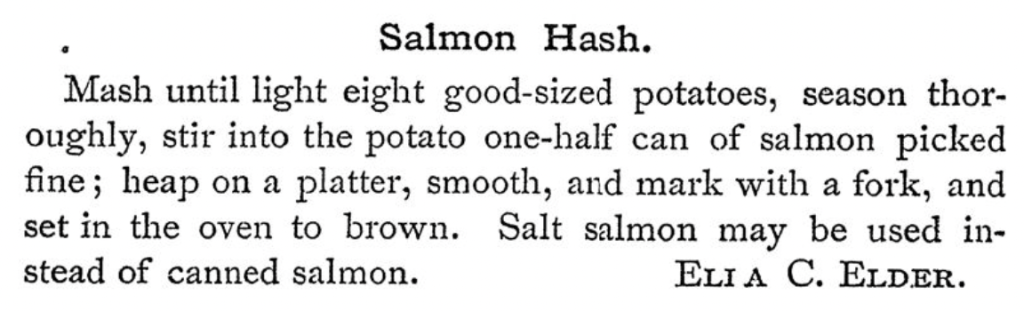

Salmon HasH

Ella C. Elder was not well-known like many of the book’s other contributors, but some internet sleuthing revealed that she was a committee member of the Free Congregational Society of Florence, Massachusetts, which was later absorbed by the Unitarian Society of Northampton and Florence. You can read the Free Congregational Society’s 1882 bylaws here.

Ingredients:

- 8 Potatoes

- 8 oz of canned salmon (approximate)

- Salt and pepper to taste

- Optional: milk, butter

Directions:

Mash the potatoes and season to taste. I like to add some butter and a little milk when I make mashed potatoes, but you could season it however you like.

Stir in the canned salmon, distributing it as evenly as possible. In the 1880s, salmon was typically distributed in one pound cans. For this recipe you want to put about half of an 1886 can, which is probably 7-8 oz. So depending on the size, add a half or a whole can. The recipe also says that you can used salt salmon instead of canned, if you prefer.

Put the mashed potatoes and salmon in an oven-safe baking dish and smooth it down with a spatula or the back of a spoon. Use a fork to make a criss-cross “hash” mark, which is supposed to help it cook evenly. Bake it in a 375 degree oven for 20-30 minutes or until golden brown on top.

The Verdict:

This is not good. I actually liked it just fine just after mixing the salmon into the mashed potatoes, but baking it just ruined the whole thing. Every bite was saturated with salmon flavor and the entire house smelled like canned fish. Nobody in my family would eat more than a couple bites. This may be an acquired taste, or perhaps the brand of salmon I used was not the best quality available, but the consensus is that if you must add canned salmon to your mashed potatoes, just skip the baking step.

In the 1880s, canned salmon in American markets were likely packed in one of the major canneries along the Columbia River in Oregon, or even shipped from canneries in British Columbia or New Brunswick, Canada. The type of salmon makes a difference in the flavor as well, so it is entirely possible that my recreation did not do Ella Elder’s recipe justice.

The Woman Suffrage Cookbook is a must read for anyone interested in women’s history and 19th-century cooking. It may not have as much culinary significance as Miss Beecher’s or The Fannie Farmer Cookbook, but it is a great time capsule of American life and a symbol of women’s fight for political independence.

Featured image: “Suffragettes with Flag” published by Bain News Service circa 1910-1915. Public domain via Library of Congress: https://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ggbain.10997/.

Sources and Further Reading

- Angelucci, Ashley. “Matilda Joslyn Gage.” National Women’s History Museum, accessed September 6, 2023. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/matilda-joslyn-gage.

- Burr, Hattie A. The Woman Suffrage Cookbook: the 1886 Classic. Mineola: Dover Publications, Inc., 2020. A republication of The Woman Suffrage Cook Book, Containing Thoroughly Tested and Reliable Recipes for Cooking, Direcrions for the Care of the Sick, and Practical Suggestions, Contributed Especially for This Work, edited and published by Hattie A. Burr, Boston, 1886.

- Colker, Madeline. “Alice Stone Blackwell.” National Park Service, accessed September 2023. https://www.nps.gov/people/alice-stone-blackwell.htm.

Love the way you have brought history alive through food. Brilliant. I never knew the movement wrote such books.

LikeLike