For my annual Halloween post, I decided to explore the wonderful world of 19th century spiritualism and throw in some food history as a bonus. Major historical movements are obviously more complex than this short post would suggest, so consider this a fun introductory overview. There are only so many hours in the day.

Religious Revivalism

A series of religious revivals in the United States, often called the “Second Great Awakening,” introduced new religions and new interpretations of Christianity that departed from traditional Calvinist theology and Catholic orthodoxy. Among these were the Disciples of Christ, the Latter-Day Saints (Mormons), and the Adventists. Revivalism affected all of the Christian faiths, with Baptists and Methodists especially seeing enormous growth in church membership. There was a general cultural shift that led to people exploring new faiths and embracing belief systems and theologies or unique blends of spiritual principles that fell outside of what was considered traditional Christianity.

Victorian Spiritualism (1848-1900)

At the same time, Victorian society’s fascination with death and elaborate mourning rituals created something of a collective obsession with grief. Child mortality was too high, life expectancy was too low, and the dark side of industrialization in Europe and the United States exposed all kinds of terrible societal problems. There were many who rejected the modern cold and clinical approach to death, so the idea of communicating with spirits and the spirit world was comforting. It was the perfect cultural and spiritual environment for another major movement (Spiritualism) to take hold.

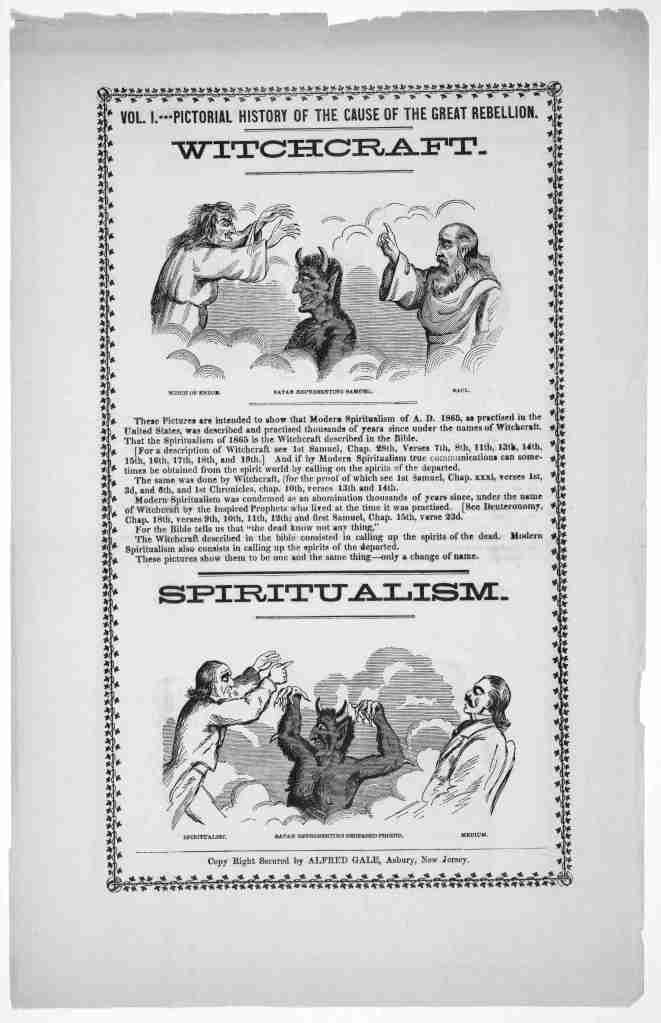

In 1848, the Fox sisters of New York claimed to speak to spirits through a series of taps or “rapping” in response to questions. Decades later they admitted to it being a hoax, but the damage was done. Séances quickly became fashionable evening entertainment, complete with table-tipping, cabinet manifestations, and spirit slates. Parlour rooms were packed with audiences eager to see a medium at work. Spiritualists offered public demonstrations and lectures, often for the benefit of skeptics hoping to expose their tricks. New technologies like photography and telegraphy were used as proof of direct communication with the spirit world.

Spiritualist demonstrations, ouija boards, and séances were certainly uniquely Victorian fads, but Spiritualism was also a belief system and area of serious study that deeply concerned many religious communities.

Image caption: 1865 Broadsheet: Vol. I. Pictorial history of the cause of the great rebellion. Public domain.

To learn more about Victorian Spiritualism from someone who lived it, you can read Emma Hardinge Britten’s 1884 book called Nineteenth century miracles, or, Spirits and their work in every country of the earth : a complete historical compendium of the great movement known as “modern spiritualism.” Let’s just call it Nineteenth Century Miracles, for short. The author was a known trance medium and women’s rights advocate.

Scientific Study

Scientists and scholars were a significant element of the Spiritualist movement. British and American societies were intrigued by scientific discovery (particularly medical science). Spiritualists welcomed empirical study of their methods, and scientists began to conduct controlled studies on mediums and the paranormal. On the one hand, Victorians hoped that these advancements might address so many of the issues plaguing the world at that time, but on the other there was a strong undercurrent of moral panic and fear of the implications. This is most notably reflected in classic horror and science-fiction literature.

The physicist Sir William Crookes tested mediums like Florence Cook and D.D. Home, as did William James, the psychologist who co-founded the American Society for Psychical Research. Charles Richet coined the term “ectoplasm,” and Camille Flammarion, an astronomer, studied levitation and investigated séances conducted by the Italian medium Eusapia Palladino. A group of Cambridge intellectuals founded the Society for Psychical Research (SPR) in 1882 to investigate ghosts, psychic mediums, and telepathy. Eleanor Sidgwick, a mathematician, was an SPR investigator who conducted critical analyses of spirit photography.

Some of these scholars became believers and defenders of Spiritualism, the most famous being Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (creator of Sherlock Holmes). Others remained skeptics. SPR investigators largely focused on exposing frauds and encouraged studying paranormal phenomena in controlled environments for this reason. Michael Faraday, the physicist known for discovering electromagnetic principles, famously created experiments to prove that table-turning was a result of unconscious muscular movements called the idiomotor effect.

Although Spiritualists like the Fox sisters and Florence Cook were exposed as frauds, some remained influential even as the spiritualist movement died down in the 20th century. But the cultural fascination with the paranormal and occult remains today.

Theosophism

The Theosophical Society was founded in 1875 by Helena Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, and William Q. Judge. This was a unique blend of Western occultism and Eastern spirituality. While there were elements of the paranormal in theosophic thought, it equally embraced science, mysticism, and religious concepts like karma and reincarnation. At the time, Theosophism was more of a philosophy than an organized religious movement. The Theosophical Society was split after Blavatsky’s death into the Theosophical Society Adyar in India (led by Olcott and Annie Besant) and the Theosophical Society of Pasadena (led by Judge and later Katherine Tingley). Both headquarters are still in operation.

Blavatsky’s Theosophism was distinct from Spiritualism but shared audiences, and many members moved between them. A major difference between the two was Spiritualists focused on communicating with spirits of the dead while Theosophists emphasized occult philosophy as wisdom and cosmic doctrine. Theosophy borrowed from Spiritualism but also resisted many of its performative demonstrations. The Theosophist monthly journal 1879-1880 provides an interesting look into the blend of beliefs and interests of the original Theosophists.

Theosophists and Vegetarianism

While it is not a requirement for Theosophists to be vegetarian, it is one of the philosophical and spiritual principles. Theosophist support for vegetarianism goes back at least to 1880: See “A Study in Vegetarianism,” an article published in the July 1880 issue of The Theosophist monthly journal.

If you are interested in 19th-century vegetarian cookery, check out the following cookbooks that have fortunately been preserved and made available online. All three books were written by known Theosophists.

- Anna Bonus Kingsford’s The Perfect Way in Diet (1881)

- Practical Vegetarian Cookery (1897) by Constance Wachtmeister

- Novel Dishes (1893) by Mary Pope. This book was reviewed in another Theosophical Society publication called Lucifer, which was edited by Annie Besant in 1894. See Page 168 of Lucifer Vol. 15.

Food and Fortunes

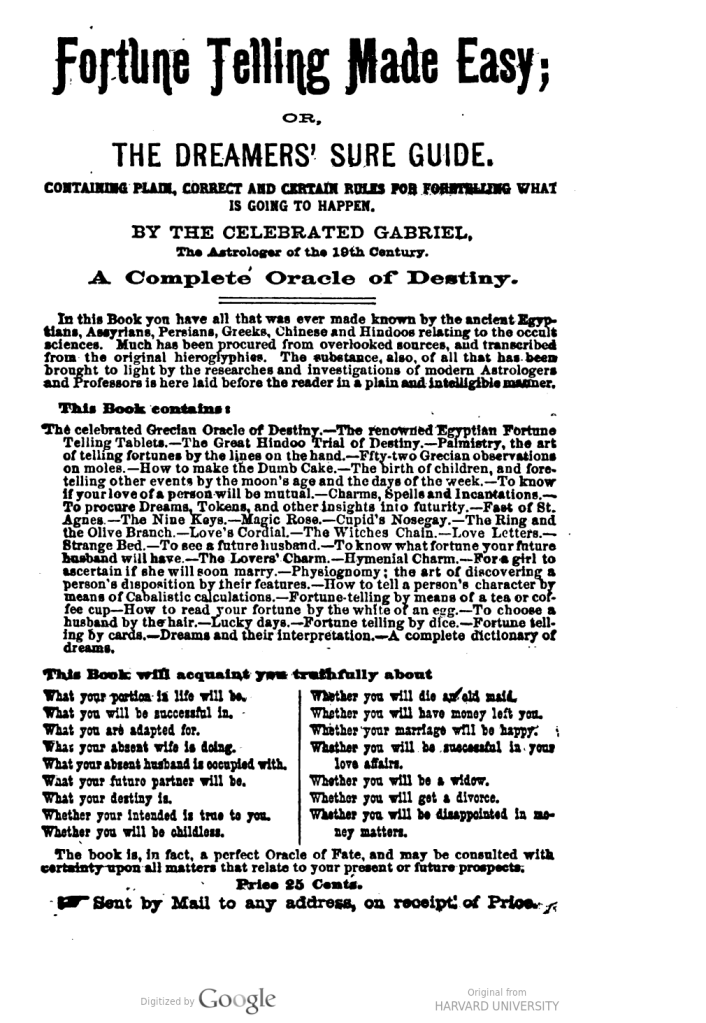

Divination and fortune telling rituals predate Spiritualism by a long-shot (centuries, even), but Victorian parlour séances did nothing but guarantee that these things would survive in the form of party games.

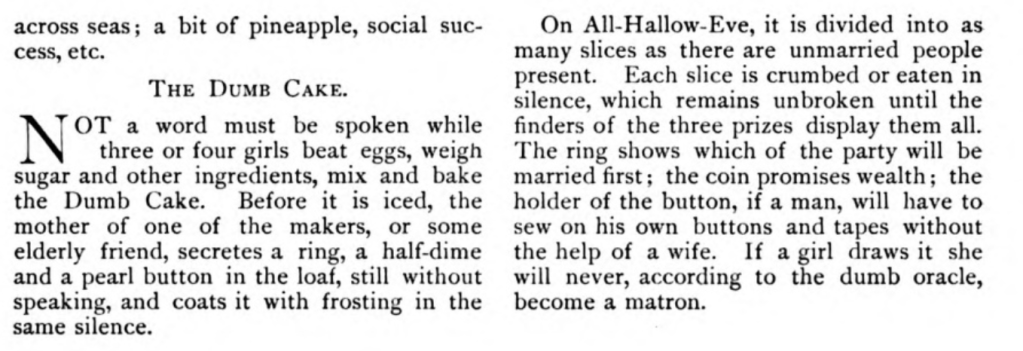

For decades, Halloween was the perfect time for young adults to conjure up a significant other at parties. I wrote a bit more about this in a past article about Hallowe’en Pumpkin Pie (1919). This was sometimes done through mirror gazing or apple bobbing, but often involved hiding objects like rings in food. Again, this kind of activity goes back centuries in Europe (medieval Kings Day feasts involved baking trinkets in cakes).

One popular divination activity, especially among teen girls, was baking an elaborate “dumb cake.” The cake had to be prepared in total silence, sometimes with specific ingredients or marking the cake with intials. In some versions, eating the cake or hiding it under a pillow would reveal the name of their future husband in their dreams.

Description of a dumb cake ritual from The Every-day book and Table book (c. 1826). Public Domain.

While Victorian Spiritualism and divination might seem like quaint relics of the 19th century, they reflect a timeless human search for meaning beyond the visible world. Whether through séances, fortune-telling, or vegetarian cooking, these movements reveal how people tried to reconcile faith, science, and everyday life in an era of change.

Cover Image: William Marriott demonstrating a levitating table. From Pearson’s Magazine March-October 1910. Public Domain.