Believe it or not, Valentine’s Day existed long before Hallmark and holiday-themed jewelry ads. Valentine greetings were popular even before roses became the “flower of love” or kindergarteners crafted valentine boxes (arguably the best activity in all of K-12).

Valentine’s Day goes back to ancient Rome and early Christianity but nobody seems to know exactly who the holiday is supposed to honor. The origin of the holiday is connected to the Roman festival Lupercalia but was adapted by Pope Galasius I in 496-ish to celebrate St. Valentine. There are at least 3 Christian saints by the name Valentine so the actual purpose of the holiday and its connection to love are a bit murky. Regardless, the holiday stuck and has been celebrated by much of the Christian world for over 1500 years. It wasn’t until 1969 that the Catholic church removed St. Valentine as one worthy of his own official feast day (Brunner), but the holiday was such an established tradition by then that many countries throughout the world continue to celebrate it, regardless of religious affiliation.

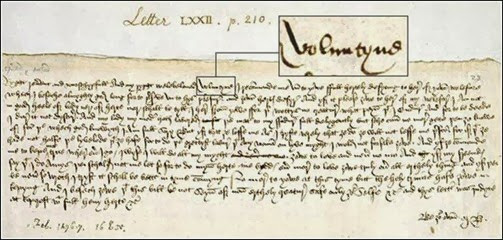

Legends vary when it comes to who wrote the first ever “valentine.” Was it the imprisoned Valentinus of ancient Rome? Or was it the imprisoned Charles, Duke of Orleans in 1415? Nobody knows for certain which, but Duke’s love letters to his wife are considered the earliest surviving written valentines and are on display in the British Museum.

First known mention of the word “valentine” in the English language!

Evolution of the Valentine

Written valentines have existed since the Middle Ages, but more often came in the form of love poetry or songs accompanied by gifts. Paper valentines became a thing in the 1500’s, and by the 1600’s it was commonplace for friends and lovers to exchange paper valentines and love notes on February 14th. This tradition was especially popular in England and Germany. Fast forward to the mid-1700’s. Hand-made paper valentines had just made their way to the United States but weren’t very widespread. Anyone willing to put in the enormous amount of effort required to make their own would have had to import fancy lace, ribbon and embossed paper from England because such materials weren’t readily available otherwise. In fact, the imported one-of-a-kind valentines themselves weren’t very affordable either. A fashionably ornate imported valentine could cost almost as much as a horse and buggy!

Since valentines weren’t yet made and sold commercially in the states, Valentine Writers became all the rage. These English-based Writers were booklets with verse-writing tips and “Be my Valentine”- esque samples. The verses could then be copied onto decorative paper and adorned with whatever else seemed appropriate. At this time men generally initiated the exchange with little love verses and the women would return with “answer” verses and so on. These valentine notes were very different from the valentines we use today. They were highly creative and deeply personal and were more like love letters than greeting cards. At the beginning of the 19th century, American-made valentines were actually available for purchase in some places, though they couldn’t hold a candle to the valentines made in England or Germany. These valentines were very simplistic black-and-white pictures painted and printed by factory workers. They weren’t very pretty and they seemed to lack that special something so there wasn’t a significant demand for them.

Beginning around 1840, Valentines came in the form of two-dimensional wood cuts or factory-made lithographs. Two of the most popular styles of valentines, at least among the minority who felt like sending them, were daguerreotype and mirror. A mirror valentine was basically a card with a mirror on it (to “see the face of the one I love” or something similarly cheesy).

AAS Online Exhibitions:

There’s evidence to suggest a man named Jotham W. Taft was personally hand-crafting pretty paper valentines with his wife and selling them as early as 1844.(Grafton News) His tiny business was somewhat of a secret due to his Quaker family’s disapproval of frivolity and, apparently, love. Despite the growing availability of American-made valentines, the tradition of actually purchasing, exchanging and mass-producing them didn’t really gain much traction in the United States until 1849 when one woman’s genius idea changed everything.

Esther Howland: “Mother of the American Valentine”

Esther was born in Worchester, Massachusetts in 1828. Her father ran a prestigious book and stationery shop, the largest in the city and most successful in the state. Esther attended Mount Holyoke Seminary in her teens and studied English grammar, history and geography. Like many of today’s graduates, Esther would end up working in a field she hadn’t majored in. But of course she didn’t know that in 1847 when she graduated.

Mount Holyoke had an unpopular and rigid rule against all things Valentine’s Day, particularly “these foolish notes called valentines.” The ban lasted for decades. Of course that didn’t stop many of the girls from secretly passing the notes around. Emily Dickinson, another Mount Holyoke graduate, famously wrote to her brother about her academic valentine plight.

In 1849 Esther received her first fancy English valentine in the mail from her father’s business associate. I can do better, she thought. She asked her father to order some linen lace and nice paper materials (such as colored paper and flowers) from his stationery suppliers in England. It took some convincing but soon she had what she needed to craft 12 sample valentines of her own. Pleased with her meticulously crafted designs, she sent them along with her brother on his business trip to New York City. Like any good brother would, he agreed to show Esther’s cards to clients. She hoped she could make $100 but to everyone’s surprise he came back with $5,000 worth of special orders! Faced with a much larger project than she had expected, she immediately set up a production room in her house and hired six friends to help. Long before Henry Ford built his first automobile Esther Howland organized an assembly line of her own, a system she believed would be the most efficient and effective way to complete the valentine orders in time.

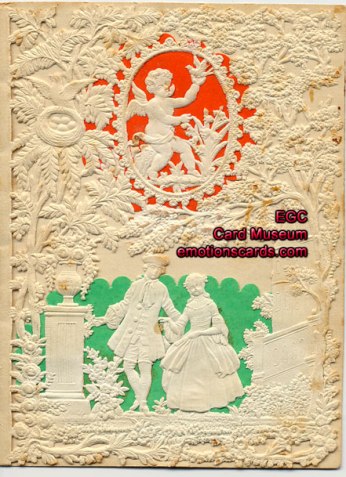

Emotionscards.com

Business grew quickly and on Feb. 5, 1850 she placed her very first ad in the local paper. Esther’s designs were beautiful and unique and nobody around could seem to compete with the quality and style of her work. Her lace valentines were especially popular, which were made using paper lace blanks she imported from England until American stationers figured out how to produce them locally. It didn’t take long before Esther’s home business grew into a valentine empire bringing in around $100,000 per year! In case you’re wondering, that is roughly equal to 3 million dollars in 2015 money. Per year.

As the company grew, so did her team. “Each girl was assigned a special task. One cut out pictures and kept them assorted in boxes. Another, with models to work from, made the backgrounds, passing them to still another who gave them further embellishment.” (Mount Holyoke News). Products were made quickly and every item was inspected by Esther personally. Throughout the 1850’s and 1860’s she managed the finances, product quality and designs herself, even down to creating the letter “H” that was stamped on the back of her cards to prevent counterfeits. She had an incredible eye and soon made some very impressive changes to her valentine designs that directly influenced the way we make stationery today.

Innovations

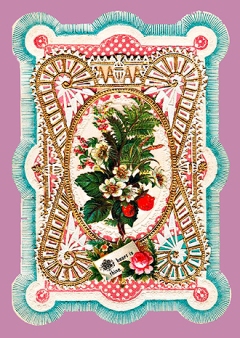

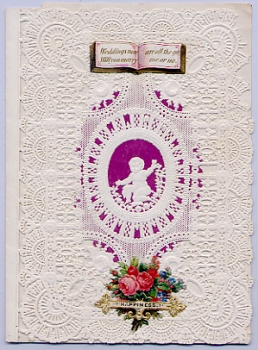

Esther was a visionary and an incredibly gifted artist. She constantly played around with new designs that had never been seen before such as hinged or lift-up flaps, die-cuts/Baxter prints, paper accordion springs, embossed overlaid flowers, shadow boxes and colorful wafer paper set behind lace to enhance the ornate patterns. Fancy little ornaments and Dresden gilt paper trimmings were proof of her incredible attention to detail. Most importantly, however, Esther developed what she called “mottos,” the valentine’s day sentiments pasted on the inside of the card. She even had over 130 verses compiled in a booklet to give her customers the opportunity to personalize their valentines!

This valentine features paper lace, numerous layers, lithograph paintings and paper springs for a shadow effect.

A Valentine Legacy

It is no wonder that the popularity of valentines soared throughout the Victorian era and beyond, thanks to Esther’s mass-produced high-quality products. As popularity for exchanging valentines grew so did Esther’s competition. But even the greatest competitors could not keep up with her. In 1879 she merged her company with small-time competitor Edward Taft, son of Jotham Taft (remember him?). Taft’s valentine-making business was based in North Grafton, a town not too far away from Worchester. Together they renamed their joint venture the New England Valentine Company. Cards were then stamped not with an “H” but with “N.E.V.Co.” After many successful years Esther Howland sold her company in 1881 to a competitor and business associate named George Whitney. The George C. Whitney Co. went on to manufacture machine-printed valentines and postcards until 1942. Esther then retired, choosing instead to care for her father in his old age. She died in 1904, having forever changed the way America- and perhaps the world- celebrated Valentine’s Day.

Though Esther Howland was not the first person to make and sell valentines in the United States, no one can argue that her designs and business savvy had an enormous impact on the valentine and greeting card industry. She was among the very first people to ever mass-produce valentines (possibly the first in the U.S.), and her products proved to be the most influential. Her innovations were long-lasting, earning her the much deserved title “Mother of the American Valentine.”

Sources and Further Reading

Note: During my research I discovered that there are many conflicting accounts regarding the history of American valentines and Esther Howland’s contribution. My response to the two common (and major) misconceptions are: 1. Esther did not create the first American valentine and 2. Valentines were manufactured and sold commercially prior to 1849 in the United States and elsewhere. Due to the surprising number of variations and details about the history of valentines, I cross-referenced every fact with a minimum of three reliable references (listed below). It is my hope that my telling of this story is as accurate as possible.

- “Making Valentines: A Tradition in America”. AAS Online Exhibitions.

- “Howland ’47 Crafts the First Mass-Produced Valentines.” Mount Holyoke News

- “Esther Howland (1828-1904)”. Victorian Treasury

- “Valentine’s Day History”. Infoplease

- History of the Card

- “The History of Greetings Cards.” Emotions Greeting Cards

- The History of Valentine’s Day. The History Channel

Sarah, this is VASTLY superior to a Wikipedia article. And more enjoyable to read. I’m so impressed with your sourcing! I wouldn’t have the patience to do it so meticulously. I’m loving this blog!!

LikeLike

Thank you Natalie! I’m so glad you enjoyed it. I love the research, it’s good for the brain box. 🙂

LikeLike

Nice work…as always. I love the details in the Howland collection. Thanks for including the examples.

LikeLike

Dear Sarah, Thank you for such a great presentation of Valentine History. My partner and I have a mass of very old materials to sort through. Our family had several large, very old collections of many sorts of cards and die cut, embossed chromo’s. The largest part of the collection consists of old valentines. It’s slow going because I want to know what I am dealing with and take the time to research as many details as practical. Your piece on Howland was great because the techniques she developed are extant in many of the older valentines we have… May I quote a short section of your piece on Howland to describe some of what we have here on Etsy etc? Of course I will give you credit and put in quotes any small section(s) presented. If this is permissible how may we reference you since web addresses in the descriptions are not permitted in our listings? We are just getting started with this labor of Love… All the Best, Joe and Mir … retrochromo.com

LikeLike

Hi Joe and Miriam, Thank you for your comment! I am happy to hear that my article and research helped you with your project. Sounds like you’ve got a lot of work ahead but I am excited for you! What a treasure it is to have such an incredible collection (I browsed your etsy shop- very cool stuff). You are certainly welcome to quote anything that is useful. You may reference me by name and/or the title of the blog, if that works. I appreciate your integrity by the way. 🙂 Good luck!

Best,

Sarah

LikeLike